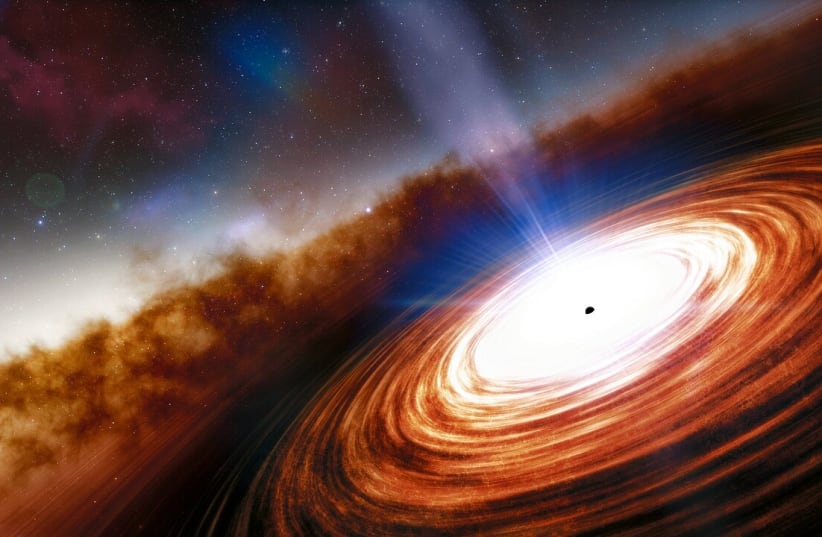

An exciting discovery could shed some light on how Earth got its water.

New observations of a disk of dust and gas circling a baby star have revealed a large amount of water vapor, at the exact location where baby planets might be starting to form.

It's the first time that astronomers have been able to map the distribution of water in a planet-forming disk around a star that might be hospitable to life.

"Our recent images reveal a substantial quantity of water vapor at a range of distances from the star that include a gap where a planet could potentially be forming at the present time," says astronomer Stefano Facchini of the University of Milan.

"I had never imagined that we could capture an image of oceans of water vapor in the same region where a planet is likely forming."

One of the big mysteries of life on Earth is where the heck our planet's water came from. Some studies suggest that a lot of Earth's water was delivered by comets and asteroids. Others suggest that Earth was born with its water, with no contribution from bombardment. Others still suggest that it's a combination of the two mechanisms.

We can't rewind time and look, but we can look at other planetary systems amid the throes of formation and see how they're doing it. And this is where a young, Sun-like star called HL Tauri, just 450 light-years away from the Solar System, is helping us out.

Stars are born in dense clouds of dust and gas. A super-dense knot in this material collapses under gravity, and starts spinning. As it spins, the material around the emerging central star arranges into a disk that circles the growing star, feeding mass into it; imagine water swirling around a drain.

Once the star has formed, any material it didn't feed on starts clumping together to form the other stuff in a planetary system, all the planets and moons and asteroids and comets. That's where HL Tauri is at now. It's less than a million years old, and surrounded by a broad, cool, stable disk.

If you look at observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), you can see that the disk has concentric gaps. Astronomers believe those gaps are carved out by planets forming, sweeping up material in the disk as they orbit the star.

Because it's so close, angled in such a way that we have a clear view of the disk, and the star HL Tauri is similar to a young Sun, and water has been detected in the disk before, Facchini and his colleagues wanted to take a closer look and figure out where precisely the water is – which is a clue about where it will eventually end up.

They took new observations of the star with ALMA, using two different wavelength bands to target water vapor. And they found a significant amount of water in the inner region of the disk, within 17 astronomical units of the star, where terrestrial planets like Earth are expected to form. That region contains at least 3.7 times as much water as can be found in all of Earth's oceans.

Even more strikingly, the water was found in a known and prominent gap in the disk. This means that there's a very good chance that water is being incorporated into any planets that may be forming there.

A recent study found that water was abundant in the Solar System before Earth formed. This first map of the spatial distribution of water in a protoplanetary disk shows that Earth could very well have been born with at least a large proportion of its water, even if some was delivered later by asteroid bombardment.

"Our results show how the presence of water may influence the development of a planetary system," Facchini says, "just like it did some 4.5 billion years ago in our own Solar System."

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/4JDEV632F5GNZBYGJ6PSR6Z5TI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/KYXW5F2S2VAH7OC24L6HNNBSAM.jpg)