Hundreds of extreme self-citing scientists revealed in new database

The world’s most-cited researchers, according to newly released data, are a curiously eclectic bunch. Nobel laureates and eminent polymaths rub shoulders with less familiar names, such as Sundarapandian Vaidyanathan from Chennai in India. What leaps out about Vaidyanathan and hundreds of other researchers is that many of the citations to their work come from their own papers, or from those of their co-authors.

Vaidyanathan, a computer scientist at the Vel Tech R&D Institute of Technology, a privately run institute, is an extreme example: he has received 94% of his citations from himself or his co-authors up to 2017, according to a study in PLoS Biology this month1. He is not alone. The data set, which lists around 100,000 researchers, shows that at least 250 scientists have amassed more than 50% of their citations from themselves or their co-authors, while the median self-citation rate is 12.7%.

The study could help to flag potential extreme self-promoters, and possibly ‘citation farms’, in which clusters of scientists massively cite each other, say the researchers. “I think that self-citation farms are far more common than we believe,” says John Ioannidis, a physician at Stanford University in California who specializes in meta-science — the study of how science is done — and who led the work. “Those with greater than 25% self-citation are not necessarily engaging in unethical behaviour, but closer scrutiny may be needed,” he says.

The data are by far the largest collection of self-citation metrics ever published. And they arrive at a time when funding agencies, journals and others are focusing more on the potential problems caused by excessive self-citation. In July, the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), a publisher-advisory body in London, highlighted extreme self-citation as one of the main forms of citation manipulation. This issue fits into broader concerns about an over-reliance on citation metrics for making decisions about hiring, promotions and research funding.

“When we link professional advancement and pay attention too strongly to citation-based metrics, we incentivize self-citation,” says psychologist Sanjay Srivastava at the University of Oregon in Eugene.

Although many scientists agree that excessive self-citation is a problem, there is little consensus on how much is too much or on what to do about the issue. In part this is because researchers have many legitimate reasons to cite their own work or that of colleagues. Ioannidis cautions that his study should not lead to the vilification of particular researchers for their self-citation rates, not least because these can vary between disciplines and career stages. “It just offers complete, transparent information. It should not be used for verdicts such as deciding that too high self-citation equates to a bad scientist,” he says.

Data drive

Ioannidis and his co-authors didn’t publish their data to focus on self-citation. That’s just one part of their study, which includes a host of standardized citation-based metrics for the most-cited 100,000 or so researchers over the past 2 decades across 176 scientific sub-fields. He compiled the data together with Richard Klavans and Kevin Boyack at analytics firm SciTech Strategies in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Jeroen Baas, director of analytics at the Amsterdam-based publisher Elsevier; the data all come from Elsevier’s proprietary Scopus database. The team hopes that its work will make it possible to identify factors that might be driving citations.

But the most eye-catching part of the data set is the self-citation metrics. It is already possible to see how many times an author has cited their own work by looking up their citation record in subscription databases such as Scopus and Web of Science. But without a view across research fields and career stages, it’s difficult to put these figures into context and compare one researcher to another.

Vaidyanathan’s record stands out as one of the most extreme — and it has brought certain rewards. Last year, Indian politician Prakash Javadekar, who is currently the nation’s environment minister, but at the time was responsible for higher education, presented Vaidyanathan with a 20,000-rupee (US$280) award for being among the nation’s top researchers by measures of productivity and citation metrics. Vaidyanathan did not reply to Nature’s request for comment, but he has previously defended his citation record in reply to questions about Vel Tech posted on Quora, the online question-and-answer platform. In 2017, he wrote that because research is a continuous process, “the next work cannot be carried on without referring to previous work”, and that self-citing wasn’t done with the intention of misleading others.

Two other researchers who have gained plaudits and cite themselves heavily are Theodore Simos, a mathematician whose website lists affiliations at King Saud University in Riyadh, Ural Federal University in Yekaterinburg, Russia, and the Democritus University of Thrace in Komotini, Greece; and Claudiu Supuran, a medicinal chemist at the University of Florence, Italy, who also lists an affiliation at King Saud University. Both Simos, who amassed around 76% of his citations from himself or his co-authors, and Supuran (62%) were last year named on a list of 6,000 “world-class researchers selected for their exceptional research performance” produced by Clarivate Analytics, an information-services firm in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which owns Web of Science. Neither Simos nor Supuran replied to Nature’s requests for comment; Clarivate said that it was aware of the issue of unusual self-citation patterns and that the methodology used to calculate its list might change.

What to do about self-citations?

In the past few years, researchers have been paying closer attention to self-citation. A 2016 preprint, for instance, suggested that male academics cite their own papers, on average, 56% more than female academics do2, although a replication analysis last year suggested that this might be an effect of higher self-citation among productive authors of any gender, who have more past work to cite3. In 2017, a study showed that scientists in Italy began citing themselves more heavily after a controversial 2010 policy was introduced that required academics to meet productivity thresholds to be eligible for promotion4. And last year, Indonesia’s research ministry, which uses a citation-based formula to allocate funding for research and scholarship, said some researchers had gamed their scores using unethical practices, including excessive self-citations and groups of academics citing each other. The ministry said that it had stopped funding 15 researchers and planned to exclude self-citations from its formula, although researchers tell Nature that this hasn’t yet happened.

But the idea of publicly listing individuals’ self-citation rates, or evaluating them on the basis of metrics corrected for self-citation, is highly contentious. For instance, in a discussion document issued last month5, COPE argued against excluding self-citations from metrics because, it said, this “doesn’t permit a nuanced understanding of when self-citation makes good scholarly sense”.

In 2017, Justin Flatt, a biologist then at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, called for more clarity around scientists’ self-citation records6. Flatt, who is now at the University of Helsinki, suggested publishing a self-citation index, or s-index, along the lines of the h-index productivity indicator used by many researchers. An h-index of 20 indicates that a researcher has published 20 papers with at least 20 citations; likewise, an s-index of 10 would mean a researcher had published 10 papers that had each received at least 10 self-citations.

Flatt, who has received a grant to collate data for the s-index, agrees with Ioannidis that the focus of this kind of work shouldn’t be about establishing thresholds for acceptable scores, or naming and shaming high self-citers. “It’s never been about criminalizing self-citations,” he says. But as long as academics continue to promote themselves using the h-index, there’s a case for including the s-index for context, he argues.

Context matters

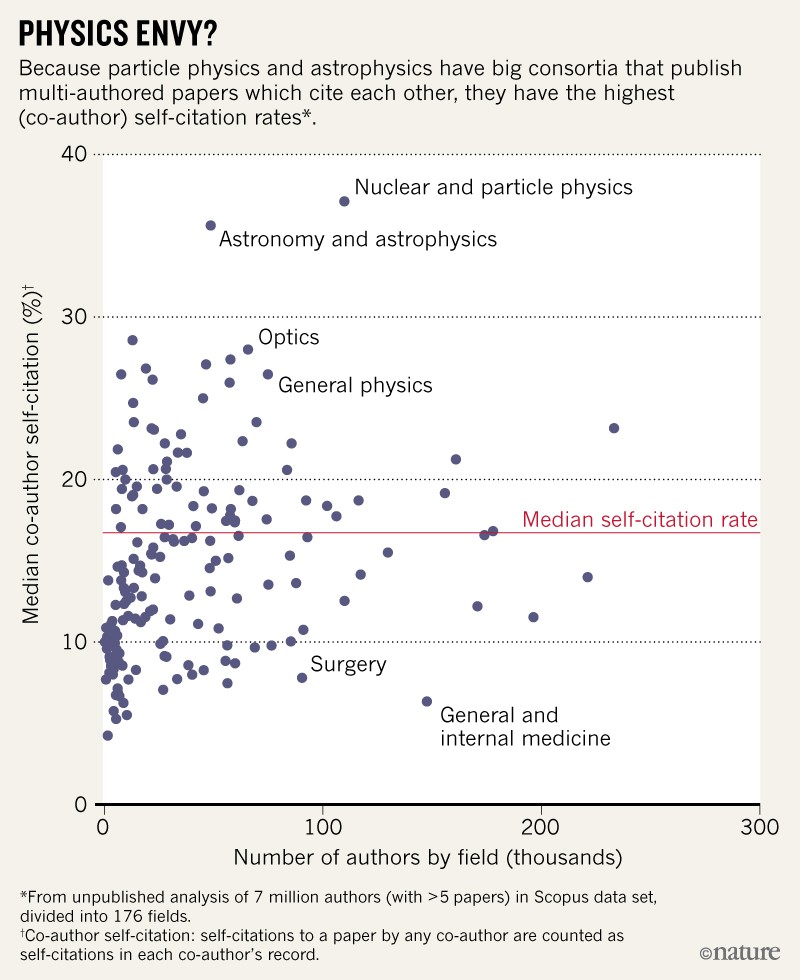

An unusual feature of Ioannidis’s study is its wide definition of self-citation, which includes citations by co-authors. This is intended to catch possible instances of citation farming; however, it does inflate self-citation scores, says Marco Seeber, a sociologist at Ghent University in Belgium. Particle physics and astronomy, for example, often have papers with hundreds or even thousands of co-authors, and that raises the self-citation average across the field.

Ioannidis says that it’s possible to account for some systematic differences by comparing researchers to the average for their country, career stage and discipline. But more generally, he says, the list is drawing attention to cases that deserve a closer look. And there’s another way to spot problems, by examining the ratio of citations received to the number of papers in which those citations appear. Simos, for example, has received 10,458 citations from only 1,029 papers — meaning that on average, he gets more than 10 citations in each paper mentioning his work. Ioannidis says this metric, when combined with the self-citation metric, is a good flag for potentially excessive self-promotion.

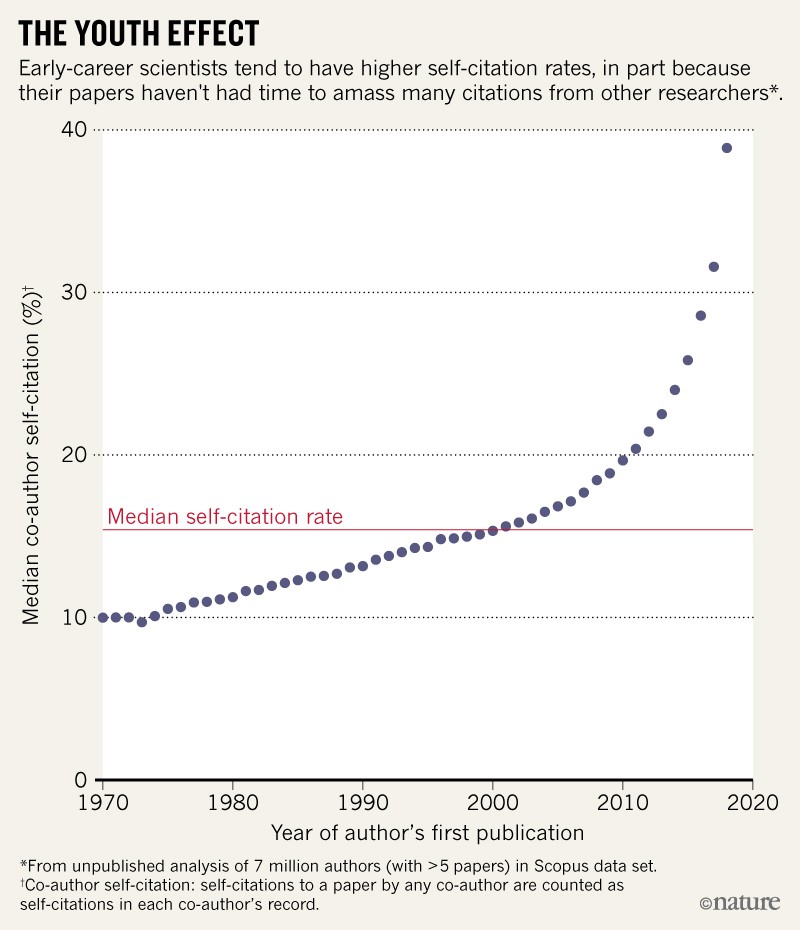

In unpublished work, Elsevier’s Baas says that he has applied a similar analysis to a much larger data set of 7 million scientists: that is, all authors listed in Scopus who have published more than 5 papers. In this data set, Baas says, the median self-citation rate is 15.5%, but as many as 7% of authors have self-citation rates above 40%. This proportion is much higher than among the top-cited scientists, because many of the 7 million researchers have only a few citations overall or are at the start of their careers. Early-career scientists tend to have higher self-citation rates because their papers haven’t had time to amass many citations from others (see ‘The youth effect’).

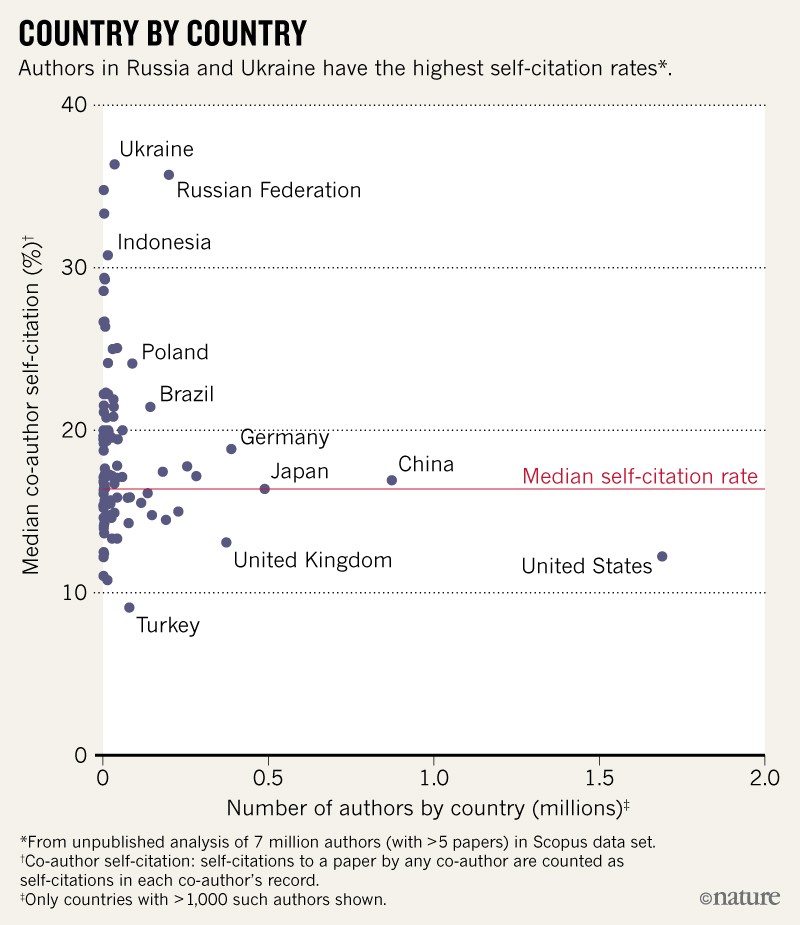

According to Baas’s data, Russia and Ukraine stand out as having high median self-citation rates (see ‘Country by country’). His analysis also shows that some fields stick out — such as nuclear and particle physics, and astronomy and astrophysics — owing to their many multi-authored papers (see ‘Physics envy?’). Baas says he has no plans to publish his data set, however.

Not good for science?

Although the PLoS Biology study identifies some extreme self-citers and suggests ways to look for others, some researchers say they aren’t convinced that the self-citation data set will be helpful, in part because this metric varies so much by research discipline and career stage. “Self-citation is much more complex than it seems,” says Vincent Larivière, an information scientist at the University of Montreal in Canada.

Srivastava adds that the best way to tackle excessive self-citing — and other gaming of citation-based indicators — isn’t necessarily to publish ever-more-detailed standardized tables and composite metrics to compare researchers against each other. These might have their own flaws, he says, and such an approach risks sucking scientists even further into a world of evaluation by individual-level metrics, the very problem that incentivizes gaming in the first place.

“We should ask editors and reviewers to look out for unjustified self-citations,” says Srivastava. “And maybe some of these rough metrics have utility as a flag of where to look more closely. But, ultimately, the solution needs to be to realign professional evaluation with expert peer judgement, not to double down on metrics.” Cassidy Sugimoto, an information scientist at Indiana University Bloomington, agrees that more metrics might not be the answer: “Ranking scientists is not good for science.”

Ioannidis, however, says his work is needed. “People already rely heavily on individual-level metrics anyhow. The question is how to make sure that the information is as accurate and as carefully, systematically compiled as possible,” he says. “Citation metrics cannot and should not disappear. We should make the best use of them, fully acknowledging their many limitations.”

doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02479-7

References

- 1.Ioannidis, J. P. A., Baas, J., Klavans, R. & Boyack, K. W. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000384 (2019).

- 2.King, M. M., Bergstrom, C. T., Correll, S. J., Jacquet, J. & West, J. D. Sociushttps://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117738903 (2017).

- 3.Mishra, S., Fegley, B. D., Diesner, J. & Torvik, V. I. PLoS ONE 13, e0195773 (2018).

- 4.Seeber, M., Cattaneo, M., Meoli, M. & Malighetti, P. Res. Policy 48, 478–491 (2019).

- 5.COPE Council. COPE Discussion Document: Citation Manipulation (COPE, 2019).

- 6.Flatt, J. W., Blasimme, A. & Vayena, E. Publications5, 20 (2017).

No comments:

Post a Comment