https://phys.org/news/2021-03-nearest-star-cluster-sun.html

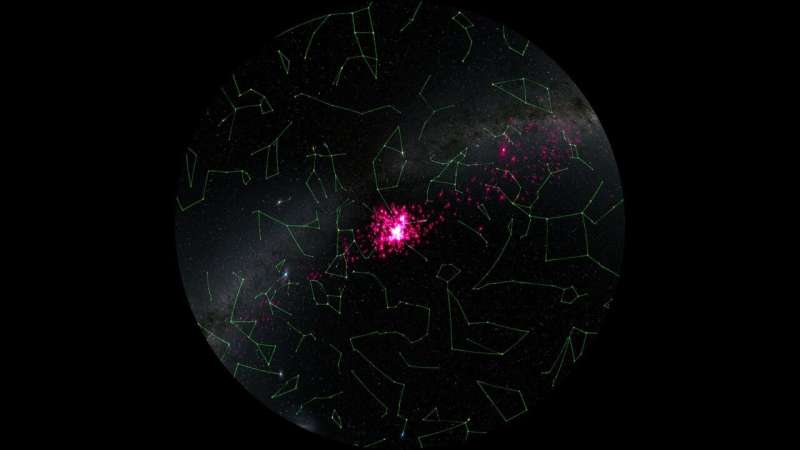

The Hyades star cluster is gradually merging with the background of stars in the Milky Way. The cluster is located 153 light years away and is visible to the unaided eye because the brightest members form a ‘V’-shape of stars in the constellation of Taurus, the Bull. This image shows members of the Hyades as identified in the Gaia data. Those stars are marked in pink, and the shapes of the various constellations are traced in green. Stars from the Hyades can be seen stretching out from the central cluster to form two ‘tails’. These tails are known as tidal tails and it is through these that stars leave the cluster. The image was created using Gaia Sky.

Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO; acknowledgement: S. Jordan/T. Sagrista.

Data from ESA's Gaia star mapping satellite have revealed tantalizing evidence that the nearest star cluster to the sun is being disrupted by the gravitational influence of a massive but unseen structure in our galaxy.

If true, this might provide evidence for a suspected population of 'dark matter sub-halos." These invisible clouds of particles are thought to be relics from the formation of the Milky Way, and are now spread across the galaxy, making up an invisible substructure that exerts a noticeable gravitational influence on anything that drifts too close.

ESA Research Fellow Tereza Jerabkova and colleagues from ESA and the European Southern Observatory made the discovery while studying the way a nearby star cluster is merging into the general background of stars in our galaxy. This discovery was based on Gaia's Early third Data Release (EDR3) and data from the second release.

The team chose the Hyades as their target because it is the nearest star cluster to the sun. It is located just over 153 light years away, and is easily visible to skywatchers in both northern and southern hemispheres as a conspicuous "V' shape of bright stars that marks the head of the bull in the constellation of Taurus. Beyond the easily visible bright stars, telescopes reveal a hundred or so fainter ones contained in a spherical region of space, roughly 60 light years across.

The true extent of the Hyades tidal tails have been revealed for the first time by data from the ESA’s Gaia mission. The Gaia data has allowed the former members of the star cluster (shown in pink) to be traced across the whole sky. Those stars are marked in pink, and the shapes of the various constellations are traced in green. The image was created using Gaia Sky.

Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO; acknowledgement: S. Jordan/T. Sagrista

A star cluster will naturally lose stars because as those stars move within the cluster they tug at each other gravitationally. This constant tugging slightly changes the stars' velocities, moving some to the edges of the cluster. From there, the stars can be swept out by the gravitational pull of the galaxy, forming two long tails.

One tail trails the star cluster, the other pulls out ahead of it. They are known as tidal tails, and have been widely studied in colliding galaxies but no one had ever seen them from a nearby open star cluster, until very recently.

The key to detecting tidal tails is spotting which stars in the sky are moving in a similar way to the star cluster. Gaia makes this easy because it is precisely measuring the distance and movement of more than a billion stars in our galaxy. "These are the two most important quantities that we need to search for tidal tails from star clusters in the Milky Way," says Tereza.

https://youtu.be/dn2Qdrz9JDo

The Hyades is an easily recognisable star cluster in the night sky. The brightest handful of stars define the face of Taurus, the Bull. Telescopes show that the central cluster itself contains many hundreds of fainter stars in a spherical region roughly 60 light years across. Previous studies have shown that stars were ‘leaking’ out of the cluster to form two tails that stretch into space. Gaia has now allowed astronomers to discover the true extent of those tails by tracing former members of the Hyades across the whole sky. The animation was created using Gaia Sky.

Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO; acknowledgement: S. Jordan/T. Sagrista.

Previous attempts by other teams had met with only limited success because the researchers had only looked for stars that closely matched the movement of the star cluster. This excluded members that left earlier in its 600–700 million year history and so are now traveling on different orbits.

To understand the range of orbits to look for, Tereza constructed a computer model that would simulate the various perturbations that escaping stars in the cluster might feel during their hundreds of millions of years in space. It was after running this code, and then comparing the simulations to the real data that the true extend of the Hyades tidal tails were revealed. Tereza and colleagues found thousands of former members in the Gaia data. These stars now stretch for thousands of light years across the galaxy in two enormous tidal tails.

But the real surprise was that the trailing tidal tail seemed to be missing stars. This indicates that something much more brutal is taking place than the star cluster gently 'dissolving."

https://youtu.be/ra3LupQjTYM

Located 153 light years away, the Hyades is between 600 and 700 million years old. During that time, stars have been ‘leaking’ out of the central cluster to form two ‘tidal tails’ that stretch across space. Gaia data has now allowed these tails to be traced across the whole sky and a mystery has been uncovered. The tails should contain roughly the same number of stars as each other but there are many more stars in the leading tail than in the trailing one. This simulation shows why that might be true. The left panel shows a schematic of the Milky Way galaxy. The Hyades star cluster is shown in yellow. The right-hand panel shows a close-up of the cluster. The grey spots show clumps of matter in the Milky Way. These could be molecular clouds, other star clusters, or clumps of dark matter termed sub-halos. As time passes, the Hyades and the other clumps orbit the centre of the galaxy. Close to the end of the simulation, one of the clumps passes through one of the Hyades tidal tails, scattering stars out of the tail.

Credit: Jerabkova et al., A&A, 2021

Running the simulations again, Tereza showed that the data could be reproduced if that tail had collided with a cloud of matter containing about 10 million solar masses. "There must have been a close interaction with this really massive clump, and the Hyades just got smashed," she says.

But what could that clump be? There are no observations of a gas cloud or star cluster that massive nearby. If no visible structure is detected even in future targeted searches, Tereza suggests that object could be a dark matter sub-halo. These are naturally occurring clumps of dark matter that are thought to help shape the galaxy during its formation. This new work shows how Gaia is helping astronomers map out this invisible dark matter framework of the galaxy.

"With Gaia, the way we see the Milky Way has completely changed. And with these discoveries, we will be able to map the Milky Way's sub-structures much better than ever before," says Tereza. And having proved the technique with the Hyades, Tereza and colleagues are now extending the work by looking for tidal tails from other, more distant star clusters.

Recommend this post and follow Sputnik's Orbit

https://disqus.com/home/forum/thesputniksorbit-blogspot-com/

Posted by Chuck in Space

No comments:

Post a Comment