https://phys.org/news/2020-09-astronomers-km-asteroid-orbiting-closer.html

This image from the study shows 2020 AV2‘s orbit. It also shows the orbits of Earth, Mercury and Venus. Perihelions are dotted lines, and aphelions are solid lines. Credit: Credit: Ip et al, 2020

Astronomers have painstakingly built models of the asteroid population, and those models predict that there will be ~1 km-sized asteroids that orbit closer to the sun than Venus does. The problem is, nobody's been able to find one—until now.

Astronomers working with the Zwicky Transient Facility say they've finally found one. But this one's bigger than predictions, at about 2 km. If its existence can be confirmed, then asteroid population models may have to be updated.

A new paper presenting this result is up on arxiv.org, a pre-press publication site. It's titled "A kilometer-scale asteroid inside Venus's orbit." The lead author is Dr. Wing-Huen Ip, a professor of astronomy at the Institute of Astronomy, National Central University, Taiwan.

The newly discovered asteroid is named 2020 AV2. It has an aphelion distance of only 0.65 astronomical units, and is about 2 km in diameter. Its discovery is surprising since models predict no asteroids this large inside Venus' orbit. It could be evidence of a new population of asteroids, or it could just be the largest of its population.

The authors write, "If this discovery is not a statistical fluke, then 2020 AV2 may come from a yet undiscovered source population of asteroids interior to Venus, and currently favored asteroid population models may need to be adjusted."

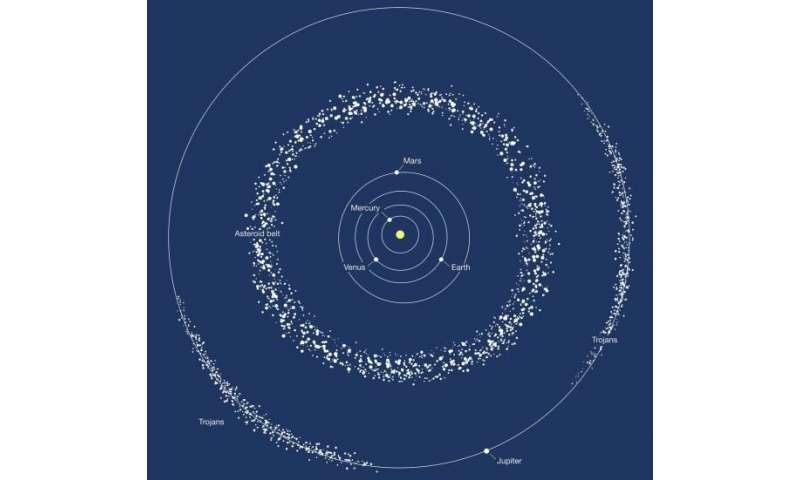

This image depicts the two areas where most of the asteroids in the Solar System are found: the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the trojans, two groups of asteroids moving ahead of and following Jupiter in its orbit around the Sun.

This image depicts the two areas where most of the asteroids in the Solar System are found: the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the trojans, two groups of asteroids moving ahead of and following Jupiter in its orbit around the Sun. Image Credit: NASA

There are about 1 million known asteroids, and the vast majority of them are well outside Earth's orbit. There are only a tiny fraction located with their entire orbits inside Earth's. Models predict that an even smaller number of asteroids should be inside Venus' orbit. Those asteroids are called Vatiras.

2020 AV2 was first spotted by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) on January 4, 2020. Follow-up observations with the Palomar 60-inch telescope and the Kitt Peak 84-inch telescope gathered more data.

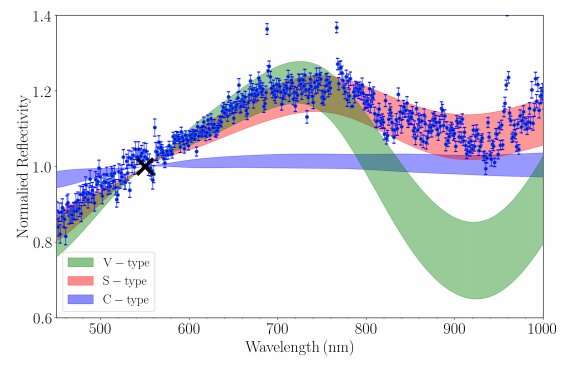

Near the end of January, astronomers used the Keck Telescope for spectroscopic observations of the rock. That data shows that the asteroid came from the inner region of the main asteroid belt, between Mars and Jupiter. "These data favor a silicate S-type asteroid-like composition consistent with an origin from the inner Main Belt where S-type asteroids are the most plentiful." They add that it agrees with Near Earth Asteroid (NEA) models that "…predict asteroids with the orbital elements of 2020 AV2 should originate from the inner Main Belt."

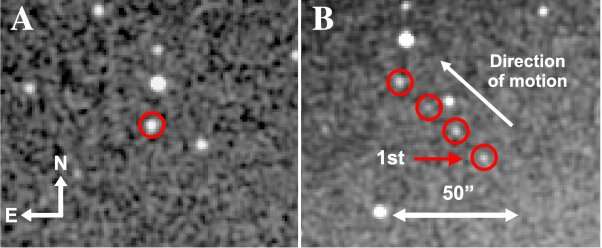

This figure from the study shows some of the images of 2020 AV2. (A) Discovery 30 s r-band image of 2020 AV2 taken on 2020 January 4 UTC where 2020 AV2 is the detection located in the circle. (B) Composite image containing the four discovery 30 s r-band exposures covering 2020 AV2 made by stack on the rest frame of the background stars over a 22 minute time interval. The first detection has been labeled. The asteroid was moving ~1 degree per day in the northeast direction while these images were being taken resulting in a ~15 arcseconds spacing between the detections of 2020 AV2.

This figure from the study shows some of the images of 2020 AV2. (A) Discovery 30 s r-band image of 2020 AV2 taken on 2020 January 4 UTC where 2020 AV2 is the detection located in the circle. (B) Composite image containing the four discovery 30 s r-band exposures covering 2020 AV2 made by stack on the rest frame of the background stars over a 22 minute time interval. The first detection has been labeled. The asteroid was moving ~1 degree per day in the northeast direction while these images were being taken resulting in a ~15 arcseconds spacing between the detections of 2020 AV2. Credit: Ip et al, 2020

2020 AV2 is either a model buster or a model confirmer. "NEA population models predict <1 inner-Venus asteroid of this size, implying that 2020 AV2 is one of the largest inner-Venus asteroids in the solar system," the authors write. It's either the largest one, which makes sense because the largest one would be the first to be spotted, or there are more of them that we haven't found yet.

The authors thought through two scenarios involving 2020 AV2's detection, and what it means. "Despite its low probability, a possible explanation for our detection of 2020 AV2 is a random chance discovery from the nearEarth asteroid population," they write. "However," they continue, "history has shown that the first detection of a new class of objects is usually indicative of another source population c.f., such as the Kuiper Belt with the discovery of the first Kuiper Belt Objects 1992 QB1 and 1993 FW."

There's also a possibility that 2020 AV2 didn't originate in the main asteroid belt. Models show that there's a region inside Mercury's orbit that could have spawned asteroids, and where they might still reside. "…2020 AV2 could have originated from a source of asteroids located closer to the sun, such as near the stability regions located inside the orbit of Mercury at ~0.1-0.2 au, where large asteroids could have formed and survived on time scales of the age of the solar system."

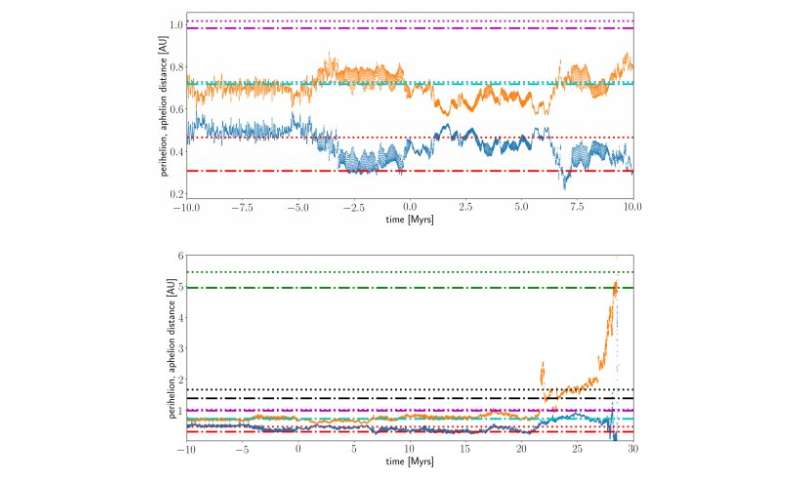

Two panels from an image in the study. The top panel shows the evolution of the aphelion (orange) and perihelion (blue) distances of 2020 AV2 integrated to ±10 Myrs. The current aphelion (dashed line) and perihelion distances (dash-dot line) are plotted as horizontal lines for Venus (cyan) and Mercury (red) and Earth (purple). The bottom panel shows the orbital evolution to 30 Myrs. The aphelion (dashed line) and perihelion distances (dash-dot line) are plotted as horizontal lines for Mars (black) and Jupiter (green). A close encounter with the Earth of ?0.01 au at ?22 Myrs and subsequent perturbations from the other planets results in 2020 AV2 eventually increasing in its aphelion distance until it encounters Jupiter and is ejected from the Solar System at ?28 Myrs.

Two panels from an image in the study. The top panel shows the evolution of the aphelion (orange) and perihelion (blue) distances of 2020 AV2 integrated to ±10 Myrs. The current aphelion (dashed line) and perihelion distances (dash-dot line) are plotted as horizontal lines for Venus (cyan) and Mercury (red) and Earth (purple). The bottom panel shows the orbital evolution to 30 Myrs. The aphelion (dashed line) and perihelion distances (dash-dot line) are plotted as horizontal lines for Mars (black) and Jupiter (green). A close encounter with the Earth of ?0.01 au at ?22 Myrs and subsequent perturbations from the other planets results in 2020 AV2 eventually increasing in its aphelion distance until it encounters Jupiter and is ejected from the Solar System at ?28 Myrs. Credit: Ip et al 2020

Spectra of 2020 AV2 obtained with the Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS) on the Keck Telescope. It shows that 2020 AV2 is an s-type siliceous asteroid, the second most common type of asteroid in the Solar System. They dominate the inner region of the main asteroid belt.

Spectra of 2020 AV2 obtained with the Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS) on the Keck Telescope. It shows that 2020 AV2 is an s-type siliceous asteroid, the second most common type of asteroid in the Solar System. They dominate the inner region of the main asteroid belt. Credit: Ip et al, 2020

When 2020 AV2 was first discovered, scientists wondered at the journey it must have taken to get there. They also wondered about is eventual fate. "Getting past the orbit of Venus must have been challenging," said George Helou, executive director of the IPAC astronomy center at Caltech and a ZTF co-investigator, in a press release. Helou explained that the asteroid must have migrated in toward Venus from farther out in the solar system. "The only way it will ever get out of its orbit is if it gets flung out via a gravitational encounter with Mercury or Venus, but more likely it will end up crashing on one of those two planets."

If this discovery is just the first of a whole population of asteroids inside Venus' orbit, the majority of them will all share the same fate. After about 10 to 20 million years, they'll all be ejected.

Recommend this post and follow

Recommend this post and follow Sputnik's Orbit

https://disqus.com/home/forum/thesputniksorbit-blogspot-com/

No comments:

Post a Comment